By Steven Jimenez

If you’ve ever taken some kind of cultural theory class, you have probably come across Subculture: The Meaning of Style by Dick Hebdige. It’s one of those texts that always gets mentioned when people try to explain punk or any kind of subcultures through sociology or media theory. Hebdige’s main argument is that subcultures use style—clothing, slang, music—as a form of articulated resistance. According to Hebdige, a particular subculture’s style communicates refusal, especially within the context of the punk rock subculture he researched. Safety pins, combat boots, torn clothes, slogans— at his time were not just about looking different, they were about making a statement.

Hebdige frames this concept using the idea of bricolage—essentially taking everyday objects and repurposing them to signal resistance. A school blazer can become an anti-school uniform. A chain wallet becomes political in the right contexts. What starts as improvised identity becomes a kind of rebellion. Eventually, he says, it all gets absorbed by popular culture. The fashion industry picks it up, the media sanitizes it, and what was once resistance becomes trendy.

There is a lot that holds up with Hebdige’s framework. It’s useful for understanding how styles can carry meaning for participants. Like how even small aesthetic choices can express broader political or social positions. However Hebdige also stops short of engaging with how these scenes actually function. Hebdige doesn’t talk about the relationships that hold everything together. He doesn’t talk about who prints the shirts, who borrows the PA, who passes out the flyers, or who had a garage where people could actually play a show.

Furthermore he refers to these groups almost exclusively in abstract terms—the punks, the mods, the scene—as if they’re fixed objects and he is analyzing from a distance. These types of things are not just aesthetic movements. These are communities! People who know each other. Friends, collaborators, roommates, ride-sharers. Reducing people and communities to a “subculture” or “the punk scene” makes it sound like we’re talking about a trend or a case study—not actual people who built something together.

That’s where I think his theory falls short. He captured the symbolic, but not the community.I can not help but read his work as interested in the gesture, but not the logistics.

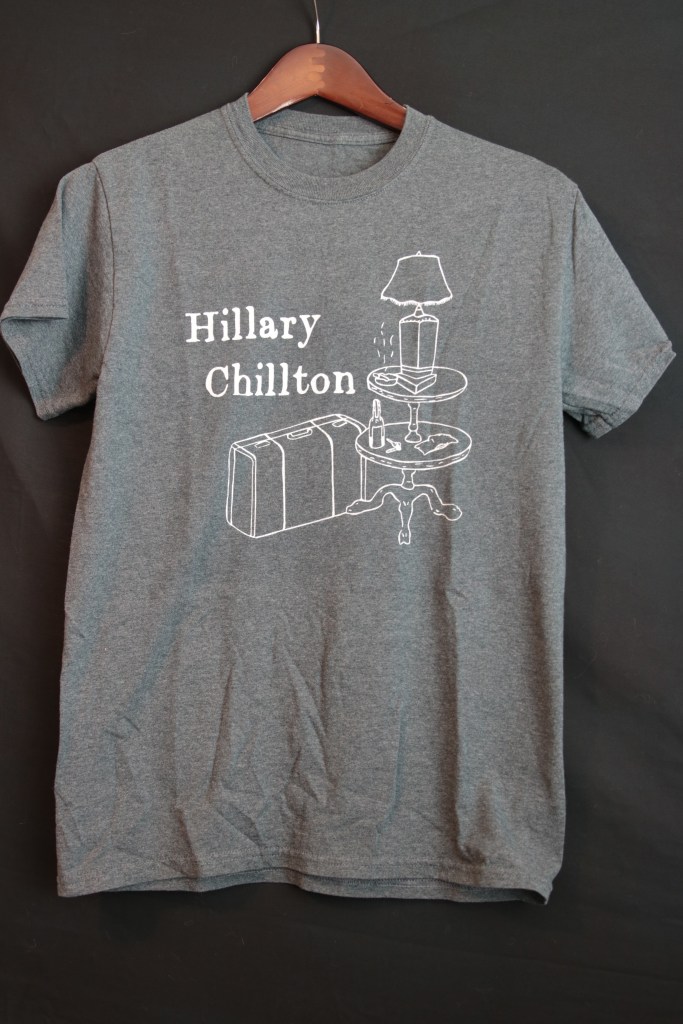

Hebdige wrote about analyzing style as resistance. However, I was always more interested in the infrastructure—how communities like ours can operate, and what remains when they don’t. WIth all of that said this collection of shirts, pins, flyers, and tapes is representative of this time in our lives. Its not just style, but tangible memory. These things are no longer identity, theyre evidence.

As far as the clothing items go, I did not save this stuff because I thought it would become important eventually. I bought them because I thought I was going to wear them.

The shirts, pins, flyers, tapes— I did not collect them necessarily with the idea of archiving and cataloging them eventually. In all reality I bought this merch to support the bands I would go to see. At this time (and even now) nobody got paid to play shows. If anything, the bands had to pay to play any kind of show! For the non pay-to-play shows, just having a place to play your music was already supposed to be the payoff. A band selling shirts or tapes is really one of the only ways to the cover costs and maybe get enough gas money for the band member that has to drive the longest, or break even on whatever you spent to get things printed, travel, or replace gear in the first place.

I gave away essentially all of the Garageland merch I ever produced —shirts, buttons, flyers—because it never made sense for me to charge one person and not another. If someone showed up and cared/supported, that was enough for me. The shirts I bought ended up folded in boxes or sitting in the closet eventually. I figured maybe one day I’d go through all of it and organize them into something. I have just never had the time.

Now that it’s been ten years I am really thankful to still have a lot of it.

Now I am working on archiving and posting these relics—not because I’m trying to relive those years, and definitely not because I’m chasing any kind of nostalgia, but more so because I think it’s worth showcasing this particular time in Southern California history. At this point, it’s a great story to tell about what happened at all of those shows in bars and backyards. It’s what the local music and arts community in Southern California looked like from around 2014 to 2018-ish. Not from a distance. From inside of it.

Archiving and cataloging these things is not about trying to make these days come back but this is also not meant to be a memorial either. It is a historical record. And in a time when it’s easy for cultural memory/history to disappear—especially when it doesn’t come from institutions or get documented through “official” channels—I think it’s worth showing what is left from that time period.

I am not trying to glorify this time or make it sound more significant than it was; however, I do not want to ignore what it meant either to myself and a lot of other people. These particular items are not souvenirs; I see them more as artifacts of a community. And now that enough time has passed, we can treat them as such.

Leave a comment